“What year is it in China?” is a question I get asked by family every now and then around Chinese New Year. Well, it’s 2020, just like in the rest of the world…

But I do understand the question very well. When I was very young, I already heard a lot about this far and mystical land called China, where fireworks were invented and pandas roam endless fresh green bamboo forests. Where my favourite Disney character Mulan (and Mushu!) came from and people apparently live in a different year. We were taught that in China, they have their own calendar and are thousands of years ahead of us.

Things were different when I moved here. China too lives in the 21st century, and none of my Chinese friends can tell me which “Chinese year” we live in. What everyone does know, is which animal this year belongs to. The year 2020 – or 4717 or 4657 in Chinese calendar that I have been told about as a child – belongs to the smallest of the Chinese Zodiac Animals, the Rat.

For this Chinese New Year, I wanted to write a blog about the Zodiac Animals, but after asking my colleagues if they knew which “Chinese year” it is, my curiosity got piqued by this ancient Chinese calendar and a whole new blog topic arose.

This article is about the history of Chinese New Year and the Chinese Calendar. Check this article if you want to read about the story of the Twelve Zodiac Animals.

If you want to read about Spring Festival in this century, check this article for Spring Festival Customs. Or read about the infamous Spring Festival Crush or how Kunming is during Spring Festival.

2020 is the year of the Rat or Mouse

2020 is the year of the Rat or Mouse

Chinese Calendar

Actually, there isn’t one “Chinese Calendar”, but many different calendar systems have been used throughout history. Often when a new king or emperor took the throne, they came up with a new calendar.

The system to point out historic events that is still used today is the Dynasty System. A Dynasty is a period of time that a specific family of rulers ruled over China. There is no set time for a Dynasty, as it lasts until another family takes over. Some span centuries and others only a few years. So, in different Dynasties, different types of calendar were introduced, based on either orbit of the sun, moon or planets or philosophical concepts such as the Five Chinese Elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal and Water).

The traditional Lunar Chinese calendar that is still used as of today to date Chinese holidays and which is celebrated during Chinese New Year was developed in the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BC). Before the Zhou Dynasty, people mainly used Solar Calendars. One version of that was a year of 365 days, divided into 5 periods of 73 days, each corresponding to one of the Five Chinese Elements. Each of those 5 periods was divided into six 12-day weeks. During other Dynasties, weeks were called xun (旬) and were 10 days long, with a resting day every five or ten days. From the 4th century and again in the 8th century, China adopted the 7-day week from the Hellenistic system.

In the Zhou Dynasty, Lunisolar Calendars based on both the sun and moon were used more commonly, even though they already existed in the Shang Dynasty (1600 – 1046 BC). What all lunisolar calendars had in common, was that months begun on the day of the New Moon. Where different calendars vary, is when the year started; the new moon at the end of the year during October or either before, after or closest to the winter solstice or spring equinox.

After the Chinese Revolution which ended in 1912 when the Qing Dynasty fell as six-year-old emperor Puyi renounced the throne, China adopted the Gregorian Calendar and adapted in 1928 to the UTC +8:00 time zone. The Lunisolar calendar was referred to as the Old Calendar or the Moon/Lunar Calendar. After 1949, it was also called the Farmer’s Calendar (Nongli 农历). All of these names, including Chinese Calendar (Zhongli 中历) can be used to refer to the Lunisolar Calendar nowadays.

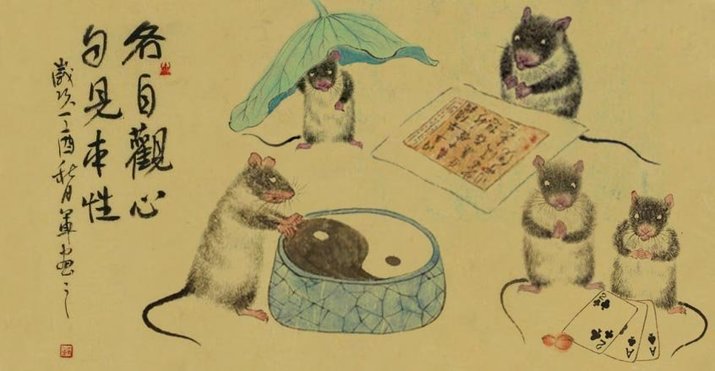

Two ancient Chinese calendars based on the moon cycle. On the right calendar, solar terms are also included.

Two ancient Chinese calendars based on the moon cycle. On the right calendar, solar terms are also included.

Chinese New Year

Today it is known almost all over the world, that Chinese New Year falls in January of February. But it wasn’t always like that.

From oracle bones dating back to the Shang Dynasty (1600 – 1046 BC), we know that people already used a lunar calendar. It is believed that people held worshipping and sacrificial ceremonies for the gods and ancestors at the end or beginning of the year. The date varied from winter solstice to beginning of spring.

From the Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 256 BC), people started to use the word nian 年 and the new year’s celebration wasn’t solely religious anymore. It became more social, and people celebrated the start of the new agricultural season and prayed for a good harvest together. Next to the ancestors and old gods, shrines to many new gods emerged, such as the wealth god, kitchen god and medicine god.

An important milestone in the history of Chinese New Year, was when the day of Chinese New Year got fixed as the first day of the first Lunar Month in the Han Dynasty (206 BC - 202 AD) by Emperor Wu (157 - 87 BC) and was called Yuandan (元旦: 元 meaning beginning and 旦 representing a new sun (日) rising from the horizon). That didn’t really mean it was fixed according to our modern calendar, because the date of the first Lunar Month still varied throughout history, ranging from the new moon before the winter solstice to the new moon around the Beginning of Spring (Lichun according to the 24 Solar Terms). The new year became a nationwide celebration and less focused on deities and ancestors and more on social life. People started to burn bamboo which would crack with loud sounds to scare away evil spirits.

Over the next centuries, Chinese New Year evolved more and more into a social event. The government organized festivities and people got free holidays to visit their family and gifting for blessings became a tradition. When in the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279) gun powder was invented, cracking bamboo was replaced by fireworks and firecrackers. In the Qing Dynasty (1636 – 1912) lion and dragon dances became very popular.

When in 1912 the Republic of China was formed, the lunar calendar got abolished and the republicans tried to establish the Gregorian Calander, which got officially adopted in 1929, with January 1st as its new New Year’s date and called Yuandan. Many people didn’t agree with it and the lunar calendar was kept for festivals and holidays. Chinese New Year was renamed Spring Festival (春节 chunjie) and by now the start of the first lunar month was fixed on the new moon closest to Lichun. Spring Festival became a national holiday in 1949, with all Chinese people getting days off to visit their family, making it the biggest human migration on earth.

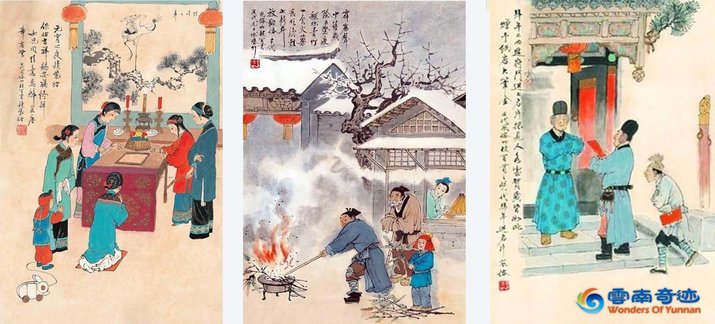

Three Ancient Chinese New Year Traditions. Worshipping gods and ancestors (left), lighting cracking bamboo as firecrackers (middle) and visiting family and gifting red envelopes or hongbaos (right)

Three Ancient Chinese New Year Traditions. Worshipping gods and ancestors (left), lighting cracking bamboo as firecrackers (middle) and visiting family and gifting red envelopes or hongbaos (right)

Months

Fairly regularly throughout Chinese history, months lasted from one New Moon to the next. This results in that months do not have a fixed length. In some years a month can have 29 days (called 小月, xiaoyue; small month) and some years that same month can have 30 days (大月, dayue; big month). There are 12 lunar months in the year, but approximately once every three years the year has a 13th month. You can calculate when a leap year will be by counting how many new moons there will in a year. This system was used until the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907), but many similar systems existed.

The first 10 days of the month get a prefix Chū (初) to them, so day 1 of the month is called Chūyī (初一) and day 10 Chūshí (初十). Days 11 to 20 are just normal numbers (shíyī 十一 is day 11) and days 21 to 29 have the prefix Niàn (廿), Niànyī (廿一) is day 21. Day 30 is also just called thirty (三十). Modern Chinese calendars still have these day names on them alongside the Gregorian Calendar dates.

Months were called after natural phenomena that marked the time of year. They were also given an Earthly Branch name (more about the Earthly Branch below), associated with the Twelve Zodiac Animals.

|

Modern Name |

Start date, between: |

Natural Name |

Earthly Branch name |

|

First Month 正月, zhēngyuè |

21 Jan – 20 Feb |

Corner Month 陬月, zōuyuè |

Tiger Month 寅月, yínyuè |

|

Second Month 二月, èryuè |

20 Feb – 21 Mar |

Apricot Month 杏月, xìngyuè |

Rabbit Month 卯月, mǎoyuè |

|

Third Month 三月, sānyuè |

21 Mar – 20 Apr |

Peach Month 桃月, táoyuè |

Dragon Month 辰月, chényuè |

|

Fourth Month 四月, sìyuè |

20 Apr – 21 May |

Plum Flower Month 梅月, méiyuè |

Snake Month 巳月, sìyuè |

|

Fifth Month 五月, wǔyuè |

21 May – 21 Jun |

Pomegranate Month 榴月, liúyuè |

Horse Month 午月, wǔyuè |

|

Sixth month 六月, liùyuè |

21 Jun – 23 Jul |

Lotus Month 荷月, héyuè |

Goat/Sheep Month 未月, wèiyuè |

|

Seventh Month 七月, qīyuè |

23 Jul – 23 Aug |

Orchid Month 蘭月/兰月, lányuè |

Monkey Month 申月, shēnyuè |

|

Eighth Month 八月, bāyuè |

23 Aug – 23 Sep |

Osmanthus Month 桂月, guìyuè |

Rooster Month 酉月, yǒuyuè |

|

Ninth Month 九月, jiǔyuè |

23 Sep – 23 Oct |

Chrysanthemum Month 菊月, júyuè |

Dog Month 戌月, xūyuè |

|

Tenth Month 十月, shíyuè |

23 Oct – 22 Nov |

Dew Month 露月, lùyuè |

Pig Month 亥月, hàiyuè |

|

Eleventh month' 十一月, shíyīyuè |

22 Nov – 22 Dec |

Winter Month 冬月, dōngyuè |

Rat Month 子月, zǐyuè |

|

End-of-year Month 臘月/腊月, làyuè |

22 Dec – 21 Jan |

Ice Month 冰月, bīngyuè |

Ox Month 丑月, chǒuyuè |

Solar Terms

The most used calendar was a lunisolar calendar, meaning it wasn’t just dependent on the moon (for months), but also on the sun’s orbit. Watching the moon’s cycle was easy, but not practical, especially for agriculture, since the moon doesn’t follow the seasons. That is why they also used the 24 Solar Terms. A year started around the Winter Solstice and the solar year was called suì (岁), which is still used when telling someone’s age (contrary to nián 年, which is now used to mark a year). The solar terms are all a 15° part from the sun’s ecliptic (the sun’s path across the sky in a year). The names are quite interesting, and like the day names, still included in modern calendars.

|

Sun’s Ecliptic |

Name |

Character |

Event |

Date (± 1 day) |

Astrology |

|

315° |

Lì chūn |

立春 |

Spring Begins |

4-Feb |

Aquarius |

|

330° |

Yǔ shuĭ |

雨水 |

Spring Showers |

19-Feb |

Pisces |

|

345° |

Jīng zhé |

惊蛰 |

Insects Awaken |

6-Mar |

Pisces |

|

0° |

Chūn fēn |

春分 |

Spring Equinox |

21-Mar |

Aries |

|

15° |

Qīng míng |

清明 |

Clear and Bright |

5-Apr |

Aries |

|

30° |

Gŭ yŭ |

谷雨 |

Wheat Rain |

20-Apr |

Taurus |

|

45° |

Lì xià |

立夏 |

Summer Begins |

6-May |

Taurus |

|

60° |

Xiǎo mǎn |

小满 |

Creatures Plenish |

21-May |

Gemini |

|

75° |

Máng zhòng |

芒种 |

Seeding Millet |

6-Jun |

Gemini |

|

90° |

Xià zhì |

夏至 |

Summer Solstice |

22-Jun |

Cancer |

|

105° |

Xiǎo shǔ |

小暑 |

Slight heat |

7-Jul |

Cancer |

|

120° |

Dà shǔ |

大暑 |

Great heat |

23-Jul |

Leo |

|

135° |

Lì qiū |

立秋 |

Autumn Begins |

8-Aug |

Leo |

|

150° |

Chǔ shǔ |

处署 |

End of Heat |

23-Aug |

Virgo |

|

165° |

Bái lù |

白露 |

White Dew |

8-Sep |

Virgo |

|

180° |

Qiū fēn |

秋分 |

Autumn Equinox |

23-Sep |

Libra |

|

195° |

Hán lù |

寒露 |

Cold dew |

8-Oct |

Libra |

|

210° |

Shuāng jiàng |

霜降 |

Frost |

24-Oct |

Scorpio |

|

225° |

Lì dōng |

立冬 |

Winter Begins |

8-Nov |

Scorpio |

|

240° |

Xiăo xuě |

小雪 |

Slight Snow |

22-Nov |

Sagittarius |

|

255° |

Dà xuě |

大雪 |

Great Snow |

7-Dec |

Sagittarius |

|

270° |

Dōng zhì |

冬至 |

Winter Solstice |

22-Dec |

Capricorn |

|

285° |

Xiăo hán |

小寒 |

Slight Cold |

6-Jan |

Capricorn |

|

300° |

Dà hán |

大寒 |

Great Cold |

20-Jan |

Aquarius |

Modern day calendars in China still have the Lunar dates and 24 Solar Terms printed on it

Modern day calendars in China still have the Lunar dates and 24 Solar Terms printed on it

Years

I finally at that point I was trying to get to. What year is it in China according to the Chinese calendar (which we found out doesn’t even exist as one system)? Well, according to some it is the year 4717, but according to other scholars and historians, it is the year 4718 or 4657. It seems that after so many millennia, dynasties and calendar systems, it is hard to keep track.

Fact is, China never knew a continuous year numbering.

But of course, they had systems to count the years, right? Yes, that’s right, and three of them were most widely used over ancient China.

Reign Names

In the Shang Dynasty (1600 – 1046 BC) the year count started and ended with the rise and fall of the emperors. The year of the ascension of a new emperor would be year 1, and the count would continue until the next emperor took the throne and reset the year count. A year would be called after the name of the emperor, followed by the number. For example, The First Emperor of the Tang Dynasty was called Tang Gaozu (唐高祖). The year he ascended the throne was called 唐高祖一年 (Tang Gaozu yinian, first year of Gaozu Tang). This counting system continued (with modifications along the way) until 1911.

Era Names

Emperor Wu from the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) created a system to number years that was also adopted all through Imperial China until the Imperial system fell and the Republic of China was founded in 1912. Instead of taking the reign of an emperor, he started to use Era names. Era names were originally two-character mottos (for example Daye 大業: The Great Endeavour) with added year number. Later new eras were inaugurated marking new beginnings for political reasons, auspicious astronomical signs or big events such as military victories to show the splendidness of the emperor. There were no set intervals for these era names, the shortest one seemed to have lasted 12 days and the longest one 61 years, though most lasted between 1 and 20 years.

When a new emperor ascended the throne, he could start a new era or continue the existing era. Some emperors had several eras throughout their reign, but from the Ming and Qing Dynasties, it became custom to have 1 era name per emperor, going parallel with the reign names. Over 800 era names were used throughout China’s history, and you can find a list of all of them on Wikipedia. Era names and reign names were carved onto coins, as you can see below.

The first coin reads clockwise, starting from the top: 淳化元宝. The first two characters read chun hua. Chun淳 means “pure” and Hua化 means “nature”. 元宝 means silver or gold ingot, but was also the name of this currency. The meaning of this era name basically means: “a beautiful world”.

The first coin reads clockwise, starting from the top: 淳化元宝. The first two characters read chun hua. Chun淳 means “pure” and Hua化 means “nature”. 元宝 means silver or gold ingot, but was also the name of this currency. The meaning of this era name basically means: “a beautiful world”.

The second is a coin from the reign of Zhenzhong, the third emperor of the Song Dynasty. Clockwise this coin says 天禧通宝. 天禧 tian xi was the era name, 通宝 tongbao means currency. Tian 天means Heavens and Xi 禧 means happiness or auspicious. This era name thus means: “auspiciousness bestowed by Heaven”.

The second is a coin from the reign of Zhenzhong, the third emperor of the Song Dynasty. Clockwise this coin says 天禧通宝. 天禧 tian xi was the era name, 通宝 tongbao means currency. Tian 天means Heavens and Xi 禧 means happiness or auspicious. This era name thus means: “auspiciousness bestowed by Heaven”.

The third coin is from the Qing Dynasty. You read it from top to bottom and right to left: 顺治通宝. The first two characters read Shunzhi, which was the name of the second emperor of the Qing Dynasty, and his reign was called after him. The other two are the currency.

The third coin is from the Qing Dynasty. You read it from top to bottom and right to left: 顺治通宝. The first two characters read Shunzhi, which was the name of the second emperor of the Qing Dynasty, and his reign was called after him. The other two are the currency.

60 Years Cycle

Those were the two simple systems. But there was another one, one that is actually still in use by some next to the Gregorian year count: the 60 Years Cycle, or also called Sexagenary Cycle, or Stems-and-Branches or Ganzhi. Wow, alright, I will go with 60 Years Cycle as it is self-explanatory almost.

As the name says, this is a cycle of sixty-year terms, that repeats itself. Each year has two Chinese characters. The first one is one of the ten Heavenly Stems and the second character is one of the twelve Earthly Branches.

Heavenly Stems

The Heavenly Stems originate from the Shang Dynasty (1600 – 1046 BC) and can be seen as ancient ordinal numbers, much like the Roman numbers I, II, III, IV, V etc. There are ten Heavenly Stems, because in that time, people believed there were ten suns, cycling in a 10-day cycle (remember the 10-day week called xun (旬) mentioned above?). The Heavenly Stems were the names of those ten suns and thus served as weekdays too. These numbers were not something to be used by the common pleb, only emperors and kings used the Heavenly Stems in their calendar because they were blessed by the Heavens.

After the Shang period, the ten Heavenly Stems became associated with the five elements and yin-yang.

|

Heavenly Stem |

Character |

Pinyin |

Original meaning |

Yin-Yang |

Element |

|

1 |

甲 |

jiǎ |

shell |

阳 yang |

木 Growing Wood |

|

2 |

乙 |

yǐ |

fishgut |

阴 yin |

木 Cut Timber |

|

3 |

丙 |

bǐng |

fishtail |

阳 yang |

火 Natural Fire |

|

4 |

丁 |

dīng |

nail |

阴 yin |

火 Artificial Fire |

|

5 |

戊 |

wù |

lance |

阳 yang |

土 Earth |

|

6 |

己 |

jǐ |

Threads on a loom |

阴 yin |

土 Earthenware |

|

7 |

庚 |

gēng |

evening star |

阳 yang |

金 Metal |

|

8 |

辛 |

xīn |

to offend superiors |

阴 yin |

金 Wrought Metal |

|

9 |

壬 |

rén |

burden |

阳 yang |

水 Running Water |

|

10 |

癸 |

guǐ |

disposed grass |

阴 yin |

水 Standing Water |

These characters are still widely used today in China as numbers on legal documents, official receipts, instead of ABC in multiple-choice questions, in organic chemistry, astrology and Fengshui to name a few.

Earthly Branches

Earthly branches are at least as old as the Heavenly Stems, dating from the Shang Dynasty. They were used for counting of hours, days, months and years. The system is derived from the orbit of Jupiter, which takes around 12 years (11.86 to be exact) to travel around the sun. Jupiter’s orbit was divided by twelve and the Earthly Branches system, and the Chinese Zodiac were associated with the twelve sections of Jupiter.

|

Earthly Branch |

Character |

Pinyin |

Chinese Zodiac |

Direction |

Season |

Lunar Month |

Time of Day |

|

1 |

子 |

zǐ |

鼠 Rat |

0° (north) |

冬 Winter |

十一月 Month 11 |

11pm to 1am |

|

2 |

丑 |

chǒu |

牛 Ox |

30° |

腊月 Month 12 |

1am to 3am |

|

|

3 |

寅 |

yín |

虎 Tiger |

60° |

春 Spring |

正月Month 1 |

3am to 5am |

|

4 |

卯 |

mǎo |

兔 Rabbit |

90° (east) |

二月 Month 2 |

5am to 7am |

|

|

5 |

辰 |

chén |

龙 Dragon |

120° |

三月 Month 3 |

7am to 9 am |

|

|

6 |

巳 |

sì |

蛇 Snake |

150° |

夏 Summer |

四月 Month 4 |

9am to 11am |

|

7 |

午 |

wǔ |

马 Horse |

180° (south) |

五月 Month 5 |

11am to 1pm |

|

|

8 |

未 |

wèi |

羊 Goat |

210° |

六月 Month 6 |

1pm to 3pm |

|

|

9 |

申 |

shēn |

猴 Monkey |

240° |

秋 Autumn |

七月 Month 7 |

3pm to 5pm |

|

10 |

酉 |

yǒu |

鸡 Rooster |

270° (west) |

八月 Month 8 |

5pm to 7pm |

|

|

11 |

戌 |

xū |

狗 Dog |

300° |

九月 Month 9 |

7pm to 9pm |

|

|

12 |

亥 |

hài |

猪 Pig |

330° |

冬 Winter |

十月 Month 10 |

9pm to 11pm |

Sexagenary Cycle

A combination of both the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches was used to count a 60-year cycle. Both would start with the first number and go down the list until the end, after which the list would start from the start again. Because there were only 10 Stems and 12 Branches, after the tenth day the 1st character from the Heavenly Stems would be combined with the 11th of the Earthly Branches and so on. This way, there were a total of 60 different combinations

|

Year |

Heavenly Stem (HS) |

Earthly Branch (EB) |

Year name |

Year name |

|

Year 1 |

HS 1 |

EB 1 |

Jiazi |

甲子 |

|

Year 2 |

HS 2 |

EB 2 |

Yichou |

乙丑 |

|

Year 10 |

HS 10 |

EB 10 |

Guiyou |

癸酉 |

|

Year 11 |

HS 1 |

EB 11 |

Jiaxu |

甲戌 |

|

Year 12 |

HS 2 |

EB 12 |

Yihai |

乙亥 |

|

Year 13 |

HS 3 |

EB 1 |

Bingzi |

丙子 |

|

Year 60 |

HS 10 |

EB 12 |

Guihai |

癸亥 |

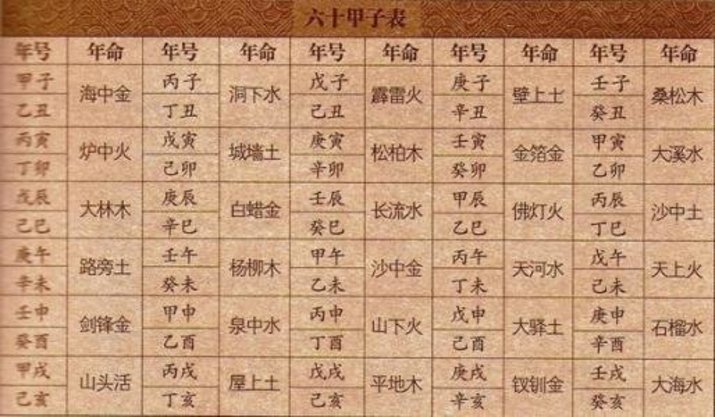

An overview of the 60 different years including elements of the Ganzhi calendar.

An overview of the 60 different years including elements of the Ganzhi calendar.

The sexagenary cycle was first used to count days beginning around 1350 BC. The first evidence for this cycle to be used to count years dates from 168 BC and was used all the way till 1912. The sexagenary Cycle was also used to count months and hours, but in a bit complex way that I will not further explain here. Check this Wikipedia article if you’re interested.

From the Shang Dynasty until now, the 60-Year Cycle was used to count years. It plays a big role in Chinese Astrology, as the Twelve Earthly Branches determine one's Chinese Zodiac Animal. During later Dynasties, this 60-Year Cycle was often combined with regal and era names. This system is still taught in schools, and Chinese pupils will get this for their exam. You can also find it on some Chinese modern calendars.

Everyone in China knows that 2020 will be the year of the Rat and that it is a Metal and Yang year. But except for astrologers, Taoists and Chinese Fortune tellers, not many will know that this is a year of Heavenly Stem geng 庚 and Earthly Branch zi 子; year 庚子, the 37th year of the cycle.

Continuous Year

So, if these three-year systems were used to count years, how did we get to the year 4717? Or confusingly to another number, 4657.

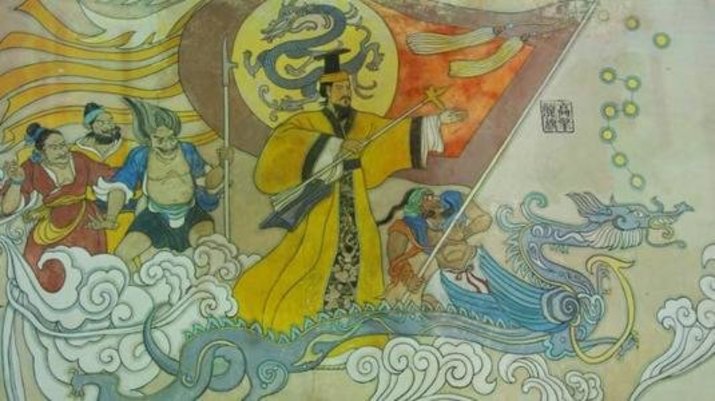

This year number originates from the Emperor Huangdi (黄帝), or also called the Yellow Emperor, who reigned from 2697 – 2597 BC. Huangdi was a real person, but many myths and legends have been written about this great national hero, who is said to have lived over a hundred years old before he ascended to the Heavens and became a deity. He is seen as the father of the new civilized China, the creator of order and government, bringer of a Golden Age.

Maybe the Yellow Emperor makes for a good blog topic for another time, but he is seen as the inventor of the 60-Year-Cycle Calendar. He invented this calendar in the 61st year of his reign, in the Gregorian year 2637 BC.

The Yellow Emperor is a legendary figure in Chinese mythology, but he has also really existed and is seen as the father of China

The Yellow Emperor is a legendary figure in Chinese mythology, but he has also really existed and is seen as the father of China

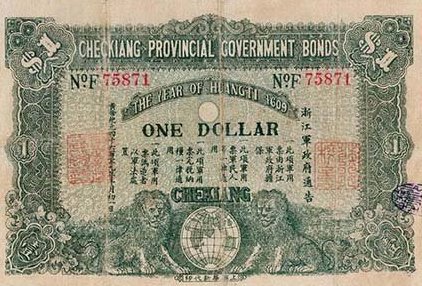

As seen above, no one in China used a continuous numbering of years, but when Western missionaries, notably Jesuit missionaries (followers of Jesus), reached China in the 16th century, they did not really agree with the Chinese idea of year numbering, as calendars just had to be continuous. And towards the end of the Qing Dynasty (1636 – 1912), Chinese Republicans wanted to detach year numbers from the emperors name, and the first president of the Republic of China Sun Yat-Sen (孫中山) was the first (and presumably also the last) to use 4609 as the year count (in 1912) when sending telegrams to leaders of foreign countries to announce the first year of the Republic of China. Sun Yat-Sen took the first year of the reign of the Yellow Emperor, the year 2697 BC, as the start of the year counting, because the Yellow Emperor had invented the 60-Year Cycle calendar system. That system wasn't related to reigns and emperors and that resonated well with the Republicans. A few documents and bills can be found, dated with the Huangti year 4609, but nothing can be found dated earlier or later.

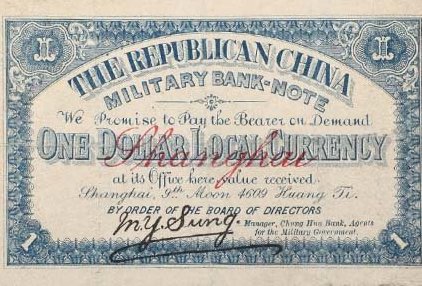

I could not find the telegram sent by Sun Yat-Sen dated 4609. However, several money bills from the year 1912 that are dated with the Huangdi year 4609 can be found. A one-dollar bill dated 4609 from the Zhejiang (Chekiang) bank (left) and a one-dollar bill from the Republican China Military Bank from Shanghai, signed by Sun Yat-Sen (right, photo from National Museum of American History)

I could not find the telegram sent by Sun Yat-Sen dated 4609. However, several money bills from the year 1912 that are dated with the Huangdi year 4609 can be found. A one-dollar bill dated 4609 from the Zhejiang (Chekiang) bank (left) and a one-dollar bill from the Republican China Military Bank from Shanghai, signed by Sun Yat-Sen (right, photo from National Museum of American History)

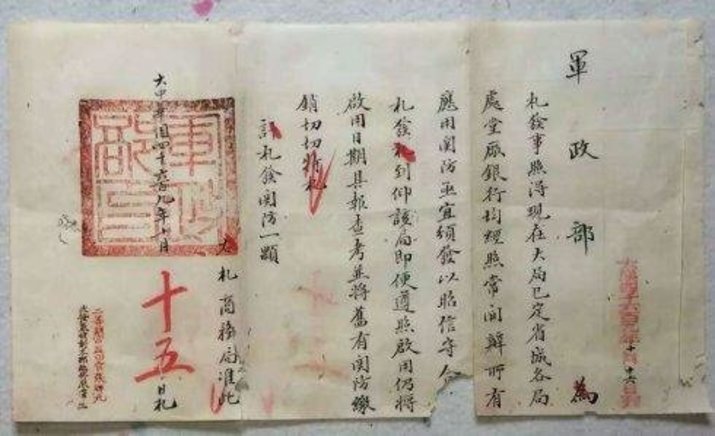

A military document, dated 4609 (四千六百零九年), issued by the military governor from the Government of Yunnan to hand over the official seal and customs defence from the Qing Dynasty to the new regime.

A military document, dated 4609 (四千六百零九年), issued by the military governor from the Government of Yunnan to hand over the official seal and customs defence from the Qing Dynasty to the new regime.

If 1912 was the year 4609, 2020 will be the year 4717. His telegram choice-of-date was adapted by many overseas Chinese communities and showed foreign leaders that China lived in another year than the West. And that is why I, as a European girl, was taught that China has a different year count and why Chinese, who since long adapted to the Gregorian year count, did not know about it.

That leaves only one question. Where does the number 4657 come from? Some scholars just take the year that Huangdi invented the calendar as the first year of the year count. Since there are exactly 60 years between the year he ascended the throne and he invented the calendar, it makes no difference for the 60-Year-Cycle system. The year of the Geng Rat is the year of the Geng Rat in both years.

And thus I can now finally explain to my family, what "Chinese year" it is and why it also actually just is 2020 like the rest of the world. I'd like to wish everyone a Happy 4717, but I guess just wishing Happy 2020 will do.

Have a Happy Chinese New Year, safe travels and enjoy the holidays!

If you are interested in more details about the Chinese Calendar, be sure to check out this book on Google Books: Chinese History, A Manual (Chapter 5, Chronology).

Further Reading about Chinese Holidays:

- 459 reads

- Like this